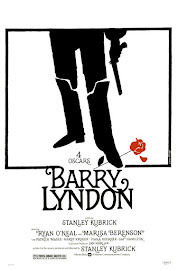

Barry Lyndon by Stanley Kubrick was the first film I loved. It was the first time I watched a film and repeated scenes on YouTube for pure aesthetic joy. Some of the scenes are so beautiful that they stand alone as pieces of art in their own right without needing to be appreciated in the context of a story. In a way, some scenes can be appreciated as if they were videos to the Schubert tracks that play in the background; music that never had videos but is deserving of something as special as what Kubrick had to offer.

The aesthetic of the film was so important to Kubrick that he had to get a special camera lenses from NASA that would work with candle-light. Only candle-light could capture the realities of 18th century lighting and provide something delicate and haunting enough to make the visual statement that Kubrick was after.

The story is about a rogue opportunist called Redmond Barry. Barry comes from the countryside of Ireland and through a series of adventures and devious activities he manages to move from relative poverty into the highest echelons of European society. Redmond becomes Barry Lyndon: his successful, cultured, socialite alter-ego.

Lyndon however is shown to be much worse at keeping money and maintaining an aristocratic lifestyle than gaining one. He is never truly accepted by elite society, who are happy to use him to achieve their ends but never sees him as an equal. The film highlights how joining the aristocratic society entails much more than simply having money; we see the saddening state of a character that cares about nothing other than achieving success in a game that requires being something different to his true nature. Lyndon achieves the wealth of an aristocrat but keeps the character and manners of a farmer boy from Ireland, and for him and most of the people around him, that is abhorrent.

Lurking in the background of the film is the light that exists beyond the darkness of human exploits. Somewhere beyond or between the wars, deceit, greed and suffering, a divine power exists and watches. We sense that a higher power is always there, making a mockery of the comical self-interest of a humanity that fails to notice that something more powerful always exists on a plane of reality where material accumulation means nothing. Kubrick achieves this effect with light: pure, natural light. Kubrick makes a statement on humanity’s place within a higher kind of existence without saying anything about it; the message is made purely with aesthetics. This is truly a great philosophical movie argued through subtle and gorgeous aesthetic symbolism.

The aesthetic of the film was so important to Kubrick that he had to get a special camera lenses from NASA that would work with candle-light. Only candle-light could capture the realities of 18th century lighting and provide something delicate and haunting enough to make the visual statement that Kubrick was after.

The story is about a rogue opportunist called Redmond Barry. Barry comes from the countryside of Ireland and through a series of adventures and devious activities he manages to move from relative poverty into the highest echelons of European society. Redmond becomes Barry Lyndon: his successful, cultured, socialite alter-ego.

Lyndon however is shown to be much worse at keeping money and maintaining an aristocratic lifestyle than gaining one. He is never truly accepted by elite society, who are happy to use him to achieve their ends but never sees him as an equal. The film highlights how joining the aristocratic society entails much more than simply having money; we see the saddening state of a character that cares about nothing other than achieving success in a game that requires being something different to his true nature. Lyndon achieves the wealth of an aristocrat but keeps the character and manners of a farmer boy from Ireland, and for him and most of the people around him, that is abhorrent.

Lurking in the background of the film is the light that exists beyond the darkness of human exploits. Somewhere beyond or between the wars, deceit, greed and suffering, a divine power exists and watches. We sense that a higher power is always there, making a mockery of the comical self-interest of a humanity that fails to notice that something more powerful always exists on a plane of reality where material accumulation means nothing. Kubrick achieves this effect with light: pure, natural light. Kubrick makes a statement on humanity’s place within a higher kind of existence without saying anything about it; the message is made purely with aesthetics. This is truly a great philosophical movie argued through subtle and gorgeous aesthetic symbolism.