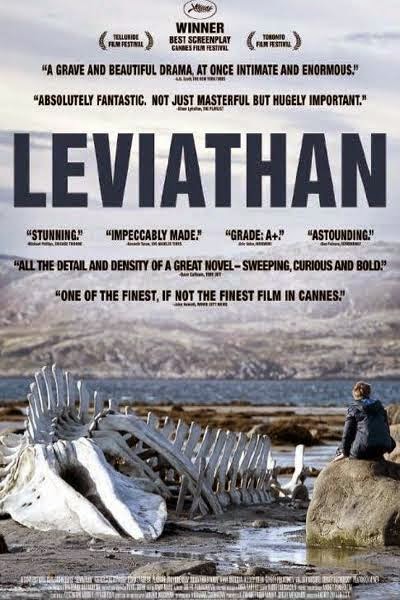

Leviathan (Directed by Andrey Zvyagintsev)/2014

The Russia we see in Leviathan is

unrelentingly corrupt. It encompasses domineering and crippling political

forces that are as entrenched and as overwhelming as the natural setting that

opens and closes this film. Zvyagintsev sets mood like not many other

directors going around. The lighting is dim and the still shots of nature pull

one into a feeling that remains throughout the rest of the movie: a feeling of

helplessness in the face of powers that structure and determine the course

of one’s life.

The Russia we see in Leviathan is

unrelentingly corrupt. It encompasses domineering and crippling political

forces that are as entrenched and as overwhelming as the natural setting that

opens and closes this film. Zvyagintsev sets mood like not many other

directors going around. The lighting is dim and the still shots of nature pull

one into a feeling that remains throughout the rest of the movie: a feeling of

helplessness in the face of powers that structure and determine the course

of one’s life.

Leviathan follows the struggles of Kolya. Kolya has lived in a modest coastal house for much of his life; it is a house built by his grandfather and handed down through the generations of his family. The local politician is trying to take the land off him so he can use it to secure votes in some manner that is not fully clear until the end of the movie. Koyla is a fighter that is not willing to bow down to the authorities. He is stubborn and willing to be crushed rather than give up some of his pride.

Koyla takes the local government to court to argue his case. He is defended by his friend from the army, Dmitri. The legal system we find is one that is swamped in bureaucracy but with no concern for the disempowered. It engages in a Kafka-esque trickery of overwhelming people with technical jargon and ostentatiousness. It ultimately prostitutes the due process to reach a verdict that affirms the powerful.

The local politician is a fat, greedy, alcoholic called Vadim. We find that he can act outside of the realm of police scrutiny and his only real threat is falling out with those even closer to the throne. At one point he arrives at Kolya’s house drunk to remind him that it is he who has the power, and if Kolya does not willingly move he will be crushed like the insect he is.

The more intriguing aspect of Leviathan is the role religion plays. The Russian Orthodox Church is shown to act in co-operation with the corrupt politicians. One of the most ironic parts of the movie is the different advice that the priest gives Kolya and Vadim. To Kolya he advises to accept the evils of life and not question why they happen; he should look to the book of Job to see how the Bible never promised a life of happiness while on earth. In contrast, he tells Vadim that he must use the power he has and not question his own actions as there is a greater good: enhancing the church’s presence. In essence, self-interest is disguised in religious statements as the priest subtlety bends Vadim to his will.

The word Leviathan is better known as Thomas Hobbes’ great work of political theory, in which he advocated the continuance of monarchy to control the evil sentiments of humanity. Obviously, this is open to exploitation when there are no structural forces in place to keep it at check.

Leviathan also appears much earlier in history in the Old Testament where Job in particular speaks of the great power of a sea monster that he deems not worth fighting. The question of whether Kolya should have just accepted his fate and resigned is a question that anyone taking on great power structures would identify with.

The strange fact about this movie is that it was partially funded by the Russian Government. It leaves the question, as to why the Russian Government would want to fund something that seems to be a complete criticism of how it is; maybe because Zvyagintsev presents religion in an equal or even worse light. The other possibility is that in funding this movie the Russian Government wanted to tell the world that there is no great structural beast rather people acting for their own individual ends.

The Russia we see in Leviathan is

unrelentingly corrupt. It encompasses domineering and crippling political

forces that are as entrenched and as overwhelming as the natural setting that

opens and closes this film. Zvyagintsev sets mood like not many other

directors going around. The lighting is dim and the still shots of nature pull

one into a feeling that remains throughout the rest of the movie: a feeling of

helplessness in the face of powers that structure and determine the course

of one’s life.

The Russia we see in Leviathan is

unrelentingly corrupt. It encompasses domineering and crippling political

forces that are as entrenched and as overwhelming as the natural setting that

opens and closes this film. Zvyagintsev sets mood like not many other

directors going around. The lighting is dim and the still shots of nature pull

one into a feeling that remains throughout the rest of the movie: a feeling of

helplessness in the face of powers that structure and determine the course

of one’s life.Leviathan follows the struggles of Kolya. Kolya has lived in a modest coastal house for much of his life; it is a house built by his grandfather and handed down through the generations of his family. The local politician is trying to take the land off him so he can use it to secure votes in some manner that is not fully clear until the end of the movie. Koyla is a fighter that is not willing to bow down to the authorities. He is stubborn and willing to be crushed rather than give up some of his pride.

Koyla takes the local government to court to argue his case. He is defended by his friend from the army, Dmitri. The legal system we find is one that is swamped in bureaucracy but with no concern for the disempowered. It engages in a Kafka-esque trickery of overwhelming people with technical jargon and ostentatiousness. It ultimately prostitutes the due process to reach a verdict that affirms the powerful.

The local politician is a fat, greedy, alcoholic called Vadim. We find that he can act outside of the realm of police scrutiny and his only real threat is falling out with those even closer to the throne. At one point he arrives at Kolya’s house drunk to remind him that it is he who has the power, and if Kolya does not willingly move he will be crushed like the insect he is.

The more intriguing aspect of Leviathan is the role religion plays. The Russian Orthodox Church is shown to act in co-operation with the corrupt politicians. One of the most ironic parts of the movie is the different advice that the priest gives Kolya and Vadim. To Kolya he advises to accept the evils of life and not question why they happen; he should look to the book of Job to see how the Bible never promised a life of happiness while on earth. In contrast, he tells Vadim that he must use the power he has and not question his own actions as there is a greater good: enhancing the church’s presence. In essence, self-interest is disguised in religious statements as the priest subtlety bends Vadim to his will.

The word Leviathan is better known as Thomas Hobbes’ great work of political theory, in which he advocated the continuance of monarchy to control the evil sentiments of humanity. Obviously, this is open to exploitation when there are no structural forces in place to keep it at check.

Leviathan also appears much earlier in history in the Old Testament where Job in particular speaks of the great power of a sea monster that he deems not worth fighting. The question of whether Kolya should have just accepted his fate and resigned is a question that anyone taking on great power structures would identify with.

The strange fact about this movie is that it was partially funded by the Russian Government. It leaves the question, as to why the Russian Government would want to fund something that seems to be a complete criticism of how it is; maybe because Zvyagintsev presents religion in an equal or even worse light. The other possibility is that in funding this movie the Russian Government wanted to tell the world that there is no great structural beast rather people acting for their own individual ends.