Carmen is one of Carlos Saura’s flamenco trilogies alongside Bodas de Sangre (Bloody Wedding) and El Amor Brujo. Set in 1980s Spain, the film follows the development of the opera Carmen performed by a flamenco dance company in almost a documentary-like style.

The film spends considerable time showing the beautiful inter-mingling of the delicate and seductive opera, Carmen, accompanied by the fierce and soulful energy of the flamenco dance and songs. It contains numerous scenes of flamenco performances and provides a glimpse into the flamenco culture as a traditional Spanish art form. The stomping heels, castanets and hand movements are amazing to watch and gets you clapping in your seat (if you’re that way inclined). So if you’re not into rhythm and dances, this film might not be for you.

I also loved the minimalist yet colourful costumes dancers wear in the film. As most of the film is set in rehearsals the dancers were not in full glitzy costumes, which can be a bit distracting, but in simple lycra outfits decorated with a volumous skirt or a drapey scarf.

The protagonist is the director of the dance company Antonio. He auditioned dozens of women, each determined to find the perfect dancer to play Carmen and he thinks he finally has. He hires Carmen. a woman of the same name as the character in the opera; a woman of mystery who seems to have no moral qualms, and is as free as a bird. He falls in love with her and he wants her to be his own. These themes of love, possession and jealousy reverberate in between the opera and the reality of Antonio’s life.

The emotions Antonio uses to perform so successfully in opera meld into his true emotions. Slowly he becomes the character and is unable to control his feelings, spiraling into a confused state between the opera and reality, which is reminiscent of the second half of the film Black Swan.

At this point the film becomes abstract as the viewers can no longer tell whether its real or the opera: exactly like how Antonio is feeling. While some viewers may find this frustrating and demand answers, I thought it was the most natural way to portray the tragic end.

This film makes a disturbing and sad viewing but it's a bitter-sweet lesson about how we treat those that are eccentric or with mental health illness.

It's set amongst a working class family in 70s Los Angeles, the husband Nick Longhetti (Peter Faulk) works for the city water works and lives with his wife Mabel (Gena Rowlands) and their 3 children.

It's not easy looking after 3 small children as well as the neighbours' kids, but Mabel takes it all in full force. She has child-like energy and earnestness, and the film does not dwell on that diagnosis the medical profession would label her with. Instead, it portrays the blurred lines between eccentricity and mental illness and how society treats her in different ways to even the most odious "normals".

Cassavete shows how people become awkard or don't know how to deal with someone that is not boring and polite. Some who are more tolerant just go with the flow and treat Mabel with respect and have a bit of fun with her. Mabel's behaviour also irks at Nick's insecurity, who constantly asks those around him: "Do you think my wife is mad?". He fails to think about how his behaviour may contribute to the chaotic surrounding, by constantly drinking and bringing in throngs of people at no notice. Because Mabel is considered "odd" any unhappiness or stress in their lives are blamed on her.

Those that think that she is mentally ill immediately see her as inferior, someone they can be rude to, someone they can tell what to do, someone they can dismiss. Or she's treated like a medical subject to be injected with serums so she can become "normal". The film shows the hypocrisy of those around Mabel in how she becomes a scapegoat for all their insecurities, jealousy, stress in their lives. People let out their anger and frustration because they think that's how she can be treated.

In the end, Nick ends up sending Mabel away to a hospital so she can be "normal". While she's away the house and childcare quickly fall apart and Nick feeds them beers to make them drowsy and behave themselves. He is desperate for her to come back and look after the household and the kids. He plans a big party for her return.

Dozens of people turn up to see Mabel return home: people from the neighbourhood who cherished her personality and energy. But Nick, in his insecurity against Mabel's popularity, shoos them away under the disguise of "Oh we don't want her to get too excited".

The returned Mabel is calm and docile: she behaves as if they would want her to behave so she doesn't have to go back to the hospital. She's lost control over her body and is subjected the to medical directions and opinions of those around her. But quiet and timid Mabel is not the Mabel Nick is used to; drunk and confused, he begs her to be normal again, to just be herself!

The title; a woman under the influence, its judgmental tone, refers to how society criticises Mabel and questions her mind. At the same time it refers to how Mabel is influenced by others: Nick's constant drinking and carousing, the mother-in-law's spying and finally, a doctor turning her into a medical subject thus forcing Mabel to relinquish autonomy over her body and mind.

Tokyo Trial is a new Netflix miniseries created in collaboration with NHK. It follows the story of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) trying the war crimes of the Japanese military post WWII. The series focuses on the Tribunal membership, the political interests revolving around the tribunal and, legal arguments that have been advanced and considered. This show is tailor made for legal historians!

The creators of the show carefully weaved the legal arguments and political influences as well as the internal battles within the tribunal. The show includes actual footage of the trial and what Japan was like at the time. The seamless movement between reality and fiction makes this show a fantastic watch as viewers get a glimpse into Japanese society at the time.

This relatively short series (only 4 episodes) was deeply thought provoking and it took me a while to gather what I wanted to say in this short review. It reminded me of what Foucault talks about in his work on Knowledge and Power. Foucault’s theory was that knowledge creates power and vice versa. Power creates knowledge in that it legitimises certain knowledge that is favourable to those in power. This dynamic plays a key role in Tokyo Trial: between the victor and the defeated; the east vs the west; the imperialists vs the colonies; the process vs the outcome; and the majority vs the dissenting.

The trial starts off with the ceremonial pomp and those in charge are determined to apply the full force of the law that had been developed after the Nuremberg trials. But how that can be legally applied as well as other intricacies of the legal arguments are quickly brushed aside. Rather, the Judges are dazzled by the international attention and become engrossed with their individual reputations and the political interests of their home nation. What follows is a sad disintegration of rule of law and a charade of “they cannot be not guilty”.

The show also subtly and beautifully portrays a broader issue facing humanity: what is modernisation and who benefits from it? A comment by the French Judge stuck in my mind: he thought that harm is justifiable if it improves people’s lives. So colonisation by western powers and the harm that occurred is justified in his mind as it was done to “improve” the lives of the people being colonised. The story gets more complicated when one of the witnesses allude to the fact that Emperor Hirohito’s plan to invade surrounding Asian nations was following the footsteps of the European countries that were able to develop and grow economically by colonising other countries: the very actions that the tribunal has set out to punish.

When you live in a world where the strong and the powerful are always right, how do you discern whether what you’re doing is in fact right? History may tell whether you were in fact right but whose perspective is that history based on? Or can you only try and hope for the best? What if your belief is based on flawed ideas? Moreover, the protagonists in the show could not conclude whether it makes sense to talk of “international” law, if the countries it applies to do not willingly enter its jurisdiction; this is the murky intersection between law and morality that no human being is able to explain, as it reaches outside the human sphere into a metaphysical one. The show leaves one with many questions to ponder around the never ending human struggle with evil and what it means to bring justice to those harmed.

This seemingly unpretentious comedy by Richard Linklater that I picked without much thought on Netflix proved to be a masterpiece of satire. The film wrestles with the ideas of justice, crime and moral decency, which all plays out among some flamboyant characters in small-town America.

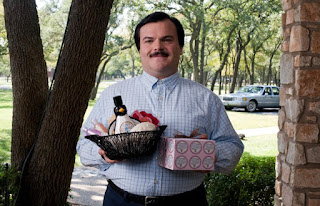

Bernie is about Bernie Tiede, a single man in his mid 30’s living in Carthage, Texas who seems to be just about perfect at everything. Jack Black is absolutely amazing in this role and I think this is by far his best performance. It really shows off his acting, comedy as well as his powerful singing. We hear of Bernie's skills, relationships and how he was “pretty much the most popular guy in town”. The movie mixes between the fictional story of Bernie as well as mockumentary-style interviews with the local people of Carthage. But alas, where there is good, there is also evil.

Bernie befriends a cranky old widow Mrs Nugent who has been left with enormous wealth following her oil baron husband’s death. Mrs Nugent is a cranky, controlling and temperamental character who has been long estranged from the children that tried to sue her. Bernie visits Mrs Nugent following the funeral of her husband to make sure she’s ok and their friendship blossoms.

The stories then diverge: some say Bernie was a manipulative gold digger, others say he is the nicest guy and was stuck in a cycle of control and abuse by Mrs Nugent who became possessive and jealous of Bernie’s popularity in town.

The central idea of criminal law is that a person is reprimanded for an act that is not condoned by society. That’s why criminal trials in America are always So-and-So vs The People of… as the particular action or offending is considered to be committed against the people. In New Zealand it’s vs “R” which signifies Regina, the Queen. This idea also follows the process of selecting jurors; people local to the community where the crime occurred are chosen to judge the actions committed by the Defendant against the community.

Often when crime is covered in the media the opinion generally divides between the good (almost always the victim) and the bad (the Defendant). Particularly in a small town, the bad are often vehemently attacked and hated by the media and public for their alleged actions. But with Bernie, people just can’t seem to get the hating right because no one can quite figure out if he is a saint or a monster. They treat him the same regardless, as humanity has so few saints that it doesn't know what to do when encountered with one.